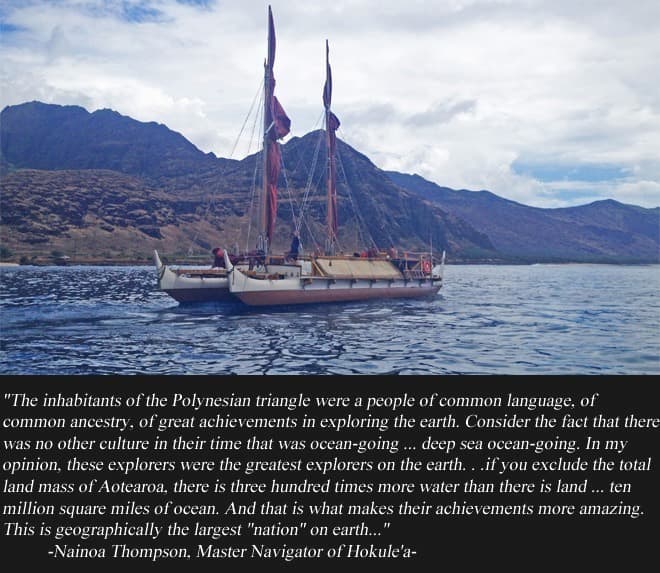

As Nainoa Thompson so eloquently stated, there was once a time when the Polynesians were the most skilled navigators on Earth.

Only 50 years ago, however, during the 1960’s, the act of Polynesian voyaging and wayfinding had been reduced to memories and lore.

There were no canoes which endured deep water sails, there were no captains who could read the map that is etched in the sun and stars, and there was no breath in the maritime spirit which one connected Polynesia.

Looking at the movement of peoples in the Pacific, the first Hawaiians were voyaging Marquesans who arrived around 400 AD. The Tahitians would arrive to supplant the Marquesans around 900 AD, and while voyages between Tahiti and the Hawaiian Islands may have existed for a short period of time, the maritime connection was eventually severed and the two nations drifted apart.

To Herb Kane, an Oahu based artist and avid paddler with an interest in Polynesian voyaging, this was an unacceptable loss of culture which couldn’t be allowed to continue. Specifically, Kane had a vision of a double-hulled sailing canoe that would voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti, and reignite the unifying spark between the people of Polynesia.

More than just a traditional canoe, however, the voyage would employ the ancient techniques of navigating, route-planning, and wayfinding. Though Kane was confident he could silent the critics, there was the fundamental problem that there was no one in Hawaii who still knew the ancient techniques.

Enter a man named Mau Pialiug, a native Micronesian who lived in the Caroline Islands on a tiny atoll named Satawal. Though the island is home to only 500 residents who subsist primarily from coconuts and fishing, it is a remote outpost where the art of wayfinding has been passed down through the generations. In 1973, a Peace Corps volunteer named Mike McCoy who had worked on the island of Satawal invited Mau to Honolulu to introduce him as a Master Navigator. It was on that journey that Mau met cultural anthropologist Ben Finney, the man who—along with Herb Kane—would become co-founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Though Mau would return to Micronesia, his involvement with Hawaii and Hokule’a had only just begun.

Enter a man named Mau Pialiug, a native Micronesian who lived in the Caroline Islands on a tiny atoll named Satawal. Though the island is home to only 500 residents who subsist primarily from coconuts and fishing, it is a remote outpost where the art of wayfinding has been passed down through the generations. In 1973, a Peace Corps volunteer named Mike McCoy who had worked on the island of Satawal invited Mau to Honolulu to introduce him as a Master Navigator. It was on that journey that Mau met cultural anthropologist Ben Finney, the man who—along with Herb Kane—would become co-founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Though Mau would return to Micronesia, his involvement with Hawaii and Hokule’a had only just begun.

With momentum building for the construction of the canoe, Hokule‘a was launched on March 8, 1975, from Kualoa on the island of Oahu. The canoe was named after the zenith star Arcturus, which passes directly overhead of the Hawaiian Islands and has been named “the star of gladness.”

With momentum building for the construction of the canoe, Hokule‘a was launched on March 8, 1975, from Kualoa on the island of Oahu. The canoe was named after the zenith star Arcturus, which passes directly overhead of the Hawaiian Islands and has been named “the star of gladness.”

From a voyaging perspective, when you see Hokule`a arc overhead, you know you’re sharing the same latitude with the Main Hawaiian Islands, and it’s a shining light in the night time heavens which helps to point the way home.

With the launch of the canoe in Kane‘ohe, Hokule‘a then sailed to the outer islands to introduce her to the Hawaiian people. Arriving in Maui at Honolua Bay—the same bay we visit and paddle during our Maui paddling tours—the presence of the canoe awakened a long dormant pride in the hearts of Polynesians. Here was a traditionally constructed voyaging canoe that not only would help to revive the craft of Polynesian voyaging, but would help to light the fires of what would be known as the Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance.

With the launch of the canoe in Kane‘ohe, Hokule‘a then sailed to the outer islands to introduce her to the Hawaiian people. Arriving in Maui at Honolua Bay—the same bay we visit and paddle during our Maui paddling tours—the presence of the canoe awakened a long dormant pride in the hearts of Polynesians. Here was a traditionally constructed voyaging canoe that not only would help to revive the craft of Polynesian voyaging, but would help to light the fires of what would be known as the Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance.

After its journey through the Hawaiian Islands, Hokule‘a experienced a groundswell of support for her upcoming voyage to Tahiti. Crew were chosen from various islands, and in 1976, along with cultural anthropologists and the master navigator Mau, Hokule‘a departed for a 2,500 mile journey without a compass or maps; this would be the first time in over 600 years that a voyaging canoe using traditional techniques would connect the Polynesian chains.

Through it all, the crew was constantly fascinated and amazed at Mau’s depth of wayfinding knowledge, and as crewmember Shorty Bertelmann put it, being around Mau and being able to glean his knowledge “was like a living ancestor that you could finally talk to. “

When Hokule‘a finally arrived in Tahiti after 31 days at sea, a crowd of over 17,000 Tahitians joined in the celebration to welcome the voyaging Hawaiians. The ancient route between Hawaii and Tahiti had once again been established, and there was living proof that the culture of Polynesia could once again live on. Watch the full length documentary Papa Mau: The Way Finder.

For as much jubilation surrounded the voyage, tragedy unfortunately lay right around the corner.

Having returned to Hawaii in 1976, another voyage was planned for 1978 between the Hawaiian Islands and Tahiti. As with the first voyage, modern conveniences were left behind in lieu of traditional methods, and on the first day of the sail, just 12 miles south of Moloka‘i, Hokule‘a was battered by gale force winds and capsized in the growing seas. Clinging to the hulls of the damaged canoe, the crew of Hokule‘a spent an uncomfortable evening adrift in the open blue.

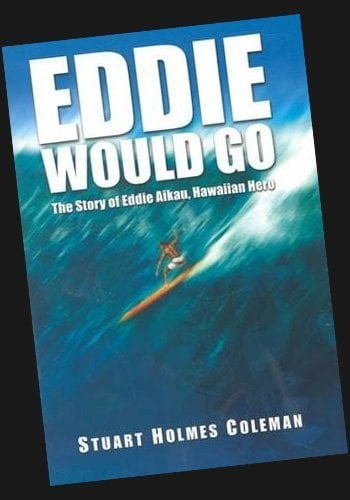

As the crew questioned if they would ever be saved, a North Shore lifeguard—Eddie Aikau—decided he would paddle a rescue surfboard in an effort to find the crew help. It is said that the lights of the Lana‘i Airport were still visible on the northern horizon, and while the crew would be saved three days later once spotted by a passing aircraft, the great surfer Eddie Aikau would never be seen again.

As the crew questioned if they would ever be saved, a North Shore lifeguard—Eddie Aikau—decided he would paddle a rescue surfboard in an effort to find the crew help. It is said that the lights of the Lana‘i Airport were still visible on the northern horizon, and while the crew would be saved three days later once spotted by a passing aircraft, the great surfer Eddie Aikau would never be seen again.

Today, Eddie is lauded for his courage and sacrifice in the face of devastating circumstance, and the full story of Eddie Aikau is masterfully chronicled in the classic biography, “Eddie Would Go,” by Stuart Coleman.

Today Hokule‘a continues to ply the Pacific and her trips have given rise to a culture of voyaging. Her sail to New Zealand inspired Maori leaders to revive the art of canoe building, and she has sailed the Pacific from Japan to Micronesia and the west coast of the Mainland U.S.

Combined with the community outreach work here at home in Hawaii, Hokule‘a has triggered a wave of awareness that is heading for international shores. The concepts of teamwork, togetherness, and looking to our ancestors for a sustainable future are principles which can apply both at home and abroad.

Combined with the community outreach work here at home in Hawaii, Hokule‘a has triggered a wave of awareness that is heading for international shores. The concepts of teamwork, togetherness, and looking to our ancestors for a sustainable future are principles which can apply both at home and abroad.

In the summer of 2014—38 years after her launch—Hokule‘a embarked on a round the world voyage to 26 countries. The voyage was entitled “Malama Honua,” which translates “to care for our Earth,” and the sail aimed to raise awareness for a peaceful and sustainable future.

Three years after sailing nearly 40,000 nautical miles around the world, the Polynesian Voyaging Society and its crewmembers returned from the Malama Honua Worldwide Voyage. An arrival ceremony and homecoming celebration took place on June 17, 2017 on Oahu’s Magic Island, with tens of thousands of people awaiting Hokule‘a’s historic return. A grand wa‘a (canoe) procession, an ancient Hawaiian spear throwing ceremony not seen in 200 years, ‘awa ceremony, hula kahiko, and musical performances were all part of the day’s celebrations.

Nainoa Thompson at the historic homecoming celebration of Hokule‘a on June 17, 2017.

As Nainoa Thompson, master navigator and president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, puts it, “these influences that we want to change and recreate for a new civil kind of society, a more healthy society, will take the work of many…when I look at all the efforts combined, I think therein lies the answer to a healthy and safe future.”