Kaho‘olawe – Sacred Island of Hawaii

Seven miles off the shore of Makena, past the crescent shape of Molokini and its famously, crystalline waters, sits an arid island on the southern horizon that visitors know little about. During our Maui paddling tours, we’re frequently asked about Kaho’olawe and its its murky military history.

“Does anybody live on the island?”

“Isn’t it covered in bombs?”

Of all the major Hawaiian Islands, Kaho’olawe has the most interesting history and is the most shrouded in mystery. And, while it might seem like an “empty” island that’s eroded, barren, and dry—Kaho’olawe is beautifully alive in more ways than you’d think.

Geologic History of Kaho‘olawe

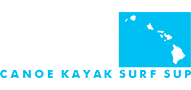

Kaho’olawe is part of Maui Nui—the original “mega-island” that comprises Maui as well as Moloka’i and Lana’i. Formed approximately 1.2 million years ago, the island was a collection of seven volcanoes that collectively covered a total land area of 5,600 square miles. To put that in perspective, that’s 50% larger than the modern day Big Island, and slightly larger than the state of Connecticut.

When sea levels rose from melting glaciers and the volcanoes slowly eroded, Maui Nui eventually was separated into the four islands we know today. Unlike Maui or Moloka’i, however, Kaho’olawe’s volcano is exceptionally low—only rising to 1,483 ft.

Consequently, it isn’t even high enough for clouds to gather around its low-lying peak, leaving it reliant on neighboring Haleakala to gather moisture and clouds.

Ancient History of Kaho‘olawe

While the exact date of settlement isn’t entirely certain, researchers believed that Ancient Hawaiians established communities on Kaho’olawe as early as 1000 A.D. Due to the scarcity of water, however, it isn’t believed that the population every numbered over a few hundred people. The main importance of Kaho’olawe, it seems, was an outdoor classroom for celestial navigation and learning to read the stars.

Through analysis of ancient Hawaiian chants and astro-archaeological findings, it’s evident that parts of the arid island were where navigators honed their skills. At the rocky summit of Moa’ulaiki, it’s possible to make out five of the seven neighboring Hawaiian Islands. Also, due to the relative distance from mountains and the island’s uniquely low profile, it’s easier to follow the track of the stars on their entire arc through the sky. At Kealaikahiki—the island’s westernmost point—this was a traditional launching point for voyaging canoes sailing all the way back to Tahiti. The name, “Kealaikahiki,” literally translates as “the road to Tahiti,” and the importance of Kaho’olawe as a navigational classroom is confirmed with each passing year.

Kaho‘olawe in the 1800’s

All of the Hawaiian island‘s many chapters, perhaps the strangest period was the time when it was used as a penal colony for prisoners. Having abolished the traditional Hawaiian religion in favor of Christianity, the Hawaiian monarchy replaced the death penalty with exile on Kaho’olawe. Though the penal colony lasted less than 30 years, it’s believed that a number of prisoners perished due to the lack of food and water.

In a handful of documented cases of survival, prisoners would literally swim all the way to the southern coast of Maui, and raid settlements for food and canoes before paddling back to the island. When the penal colony closed in 1858, a series of fledgling ranching ventures were started with little success, and during this time over 50,000 goats would destroy the island’s vegetation.

US Navy Bombing Range

Then, on the fateful morning of December 8, 1941, the future of the island of Kaho’olawe would be forever changed. The day prior, when Japanese bombers emptied their payloads on the warships stationed at Pearl Harbor, they set in motion a chain of events that would eventually lead to Martial Law being declared in all of Hawaii.

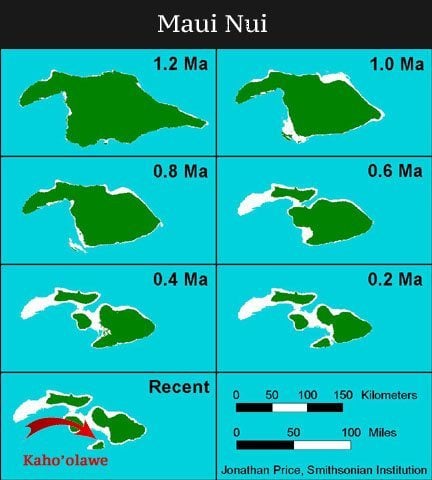

One of the acts of that Martial Law was that Kaho’olawe was immediately controlled as a target island for bombing. The location, it’s said, was perfect for a military training to fight a new kind of enemy in the Pacific. Over the course of World War II—and 45 years that would follow—thousands of bullets, mortars and bombs would deplete the little topsoil remaining on the already eroded island.

Operation Sailor’s Hat

Of all the bombing on Kaho’olawe, none is more infamous than the series of bombings in 1965. Collectively known as “Operation Sailor Hat,” the blasts contained 500 tons of explosives meant to simulate a nuclear bomb. Warships were anchored immediately offshore, and the purpose of the tests was to determine how a blast of a nuclear-strength would affect a U.S. warship. There was no radiation involved in the tests—although the strength of the blasts on the island’s coast resulted in a crater over 280 feet in diameter.

Known today as the “Sailor Hat Crater,” the crater now houses an anchialine pool that’s home to ‘opae’ulashrimp found mainly in brackish ponds.

1970’s Controversies

Throughout the bombing of Kaho’olawe, it’s safe to say that not everyone was pleased with what was taking place on the island. For many of Hawaii’s Native Hawaiians, the bombing of such an historic and sacred place was a desecration of Hawaiian culture. In addition to the strafing and pillaging of the Earth, 1,000 years of archaeology was literally disappearing from the face of the Earth with every payload dropped.

Which is why, in highly publicized political events meant to draw attention to the island, demonstrators with the Protect Kaho’olawe Ohana placed themselves ashore in 1976. Because the island was Federal property and the site of unexploded ordnance, no civilians were allowed to access the island at any time. On the morning of January 5th, however, nearly 100 protesters departed from Ma’alaea harbor en route to Kaho’olawe. It didn’t take long for U.S. Coast Guard boats to intercept the majority of protestors, but one boat carrying nine of the protesters was able to reach the shore. By afternoon, seven of the protestors were apprehended and released back on Maui, although two were able to survive for two nights before eventually turning themselves in.

A year later, in 1977, the political battle for Kaho’olawe would take a deadly turn. While en route to pick up two protestors who had been ashore for 35 days, three protestors by the names of George Helm, Kimo Mitchell, and unrelated Billy Mitchell, were stranded on the island when their rescue boat was mysteriously damaged on Maui. With only two surfboards between the three of them, Billy Mitchell turned back for help when he realized the currents were too strong. Tragically, the plea for help would come too late, and George Helm and Kimo Mitchell were never seen again.

The End Of Bombing, Reforestation, and Cultivating Hawaiian Culture

After the death of Helm and Kimo Mitchell, pressure to return the Hawaiian island reached a feverish pitch. Despite the mounting protests, however, bombing continued unabated for another 13 years.

Finally, in 1990, President George Bush issued an immediate end to live fire training on Kaho’olawe, and in 1994, the island was returned from the U.S. Navy back to the state of Hawaii. For the next decade, the U.S. Navy would spend $400 million cleaning unexploded ordnance from the island, and when they handed control to the Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commissionin 2004, 75% of the island’s surface had been marginally cleaned of ordnance.

Today, the future of Kaho’olawe is as uncertain as the mysteries surrounding its past. Volunteer efforts at reforestation have taken place for over a decade, although the lack of topsoil and fresh water continues to present a challenge. The island is used for educational outings and Hawaiian cultural practices, but a depletion of funds has left many questioning how long the outings will continue.

In spite of the very real challenges, however, many feel that Kaho’olawe is the zenith star that’s lighting the way towards Hawaiian cultural revival. Navigators for Hokule’a have trained here—studying the path of the stars—and there’s the hope that the island will be an outdoor classroom for traditional practices and values.

Regardless of what the future may hold, there is an energy, or mana, to Kaho’olawe, that has gone dormant on the neighboring Hawaiian Islands from modern commercial development. Despite the years of incessant bombing and the violent scorching of Earth, the island—ironically—was spared from the development and is beautifully empty today. In the literal as well as figurative sense, Kaho’olawe is like an enormous time capsule and a portal to Hawaii’s past.

Most recently, supporters of the Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission have launched a funding campaign in an effort to ensure continued restoration of and access to the island. As of Friday, June 5th, the group has raised less than a third of the campaign goal is to raise $100,000 in 30 days. The Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission has pledged to provide for the meaningful and safe use of Kaho’olawe for the purpose of the traditional and cultural practices of the native Hawaiian people. Its mission is to implement the vision for Kaho’olawe Island in which to undertake the restoration of the island and its waters. In May, the Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission hosted a Kako’o ia Kaho’olawe Work Day where volunteers made an active contribution to the restoration of Kaho’olawe by working on the walking trail and native plant nursery. An 8-acre parcel of Kaho’olawe was designated to Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission in 2002 as the future site of a Kaho’olawe learning center.

Aside from the petroglyphs and archeological sites that managed to survive the bombing, the island offers a way of life that’s rooted in natural surroundings. Here on the shores of this “empty” island, the stars at night shine a little bit brighter and the waves lap a little bit louder, and an entire culture is filled with hope for what the island’s future might hold.